I used to be a chronic over-explainer.

Back when I was cutting my teeth on fantasy writing, I’d spend pages detailing my magic systems. I’d explain exactly how the political structure worked, why the currency was called “drakes,” and the precise geological formation that created the floating islands. I thought more detail meant better worldbuilding.

Turns out I was suffocating my stories.

The wake-up call came when a beta reader told me they’d skipped three pages of my “brilliant” economic exposition to get back to the characters. That hurt, but it taught me something crucial about soft worldbuilding – sometimes the details you don’t include are more powerful than the ones you do.

Soft worldbuilding isn’t about being lazy or vague. It’s about understanding that your job isn’t to build a world. It’s to create the illusion of a world that extends beyond the boundaries of your story. And sometimes, that means trusting your readers to fill in the blanks.

Most writing advice treats worldbuilding like architecture – you need blueprints, structural engineering, and detailed plans before you can build anything worthwhile. But what if worldbuilding is more like painting? What if the negative space, the areas you leave untouched, are just as important as the brushstrokes you make?

This approach isn’t just valid. For many stories, it’s superior. It creates engagement instead of exposition dumps. It builds atmosphere instead of encyclopedias. And it keeps your readers turning pages instead of taking notes.

Let me show you how to master this approach and why it might be exactly what your story needs.

Hard vs. Soft: Understanding the Spectrum

Here’s the thing about the hard worldbuilding vs. soft worldbuilding debate – it’s built on a false premise. Writers act like you have to choose between being Tolkien or being intentionally mysterious. That’s bullshit.

Worldbuilding exists on a spectrum, not in two rigid camps.

Even Tolkien, the patron saint of detailed worldbuilding, practiced soft worldbuilding more than most people realize. Sure, he had extensive notes about Middle-earth’s languages and history. But readers of The Lord of the Rings didn’t need to know the difference between Quenya and Sindarin to get invested in the story. They experienced the depth through hints, songs, and casual references that suggested vast knowledge without dumping it on the page.

When Gandalf mentions the “seven stars and seven stones and one white tree,” he’s not stopping to explain the political significance of Gondor’s ancient symbols. He’s creating the feeling of deep history through suggestion. That’s soft worldbuilding at work.

Compare this to Brandon Sanderson’s approach with his magic systems. Sanderson gives you rules, limitations, and clear cause-and-effect relationships. That’s hard worldbuilding, and it serves his plot-driven narratives perfectly. But even Sanderson doesn’t explain everything. He might detail how Allomancy works, but he doesn’t bore you with the metallurgy behind pewter production.

On the other side, Terry Pratchett’s Discworld operates on comedic logic and satirical conventions. Magic works because it’s funny or makes a point about our world. That’s soft worldbuilding that prioritizes theme and humor over systematic consistency.

The key is matching your approach to your story’s needs.

If you’re writing a heist where the magic system is central to your plot mechanics, you probably need harder worldbuilding. If you’re writing a character study set in a magical world, you might want softer worldbuilding that creates atmosphere without overwhelming the emotional journey.

The sweet spot for most stories lies somewhere in the middle – what I call “firm worldbuilding.” You establish clear rules and consistent details for the elements that matter to your plot and characters, while leaving everything else as suggestion and implication.

Your worldbuilding should feel like an iceberg. Ninety percent of it stays hidden beneath the surface, but that invisible mass gives weight and stability to the ten percent your readers can see.

The Three Pillars of Effective Soft Worldbuilding

Pillar 1: Selective Detail

The iceberg principle doesn’t mean you build less. It means you show less.

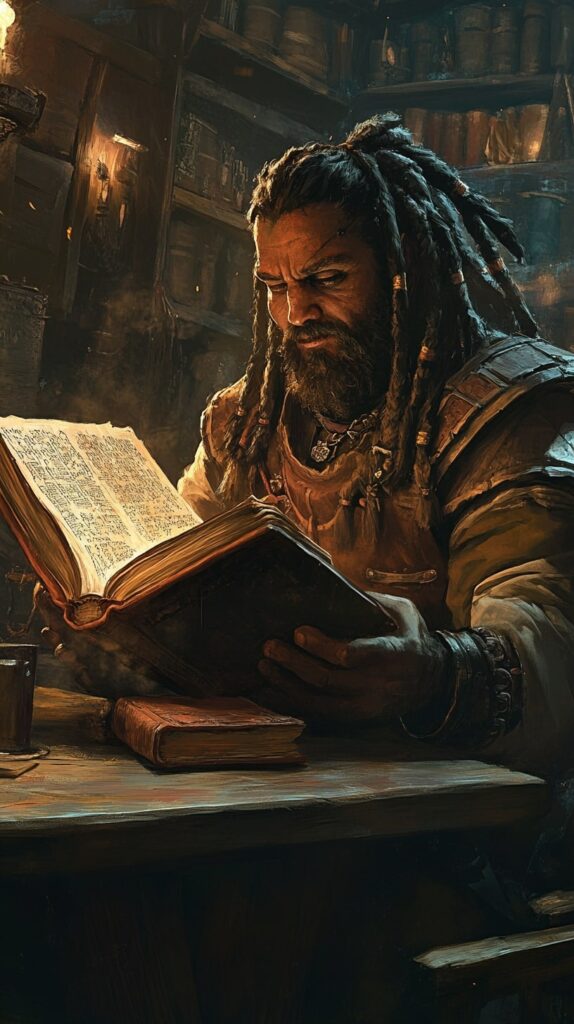

Effective soft worldbuilding requires just as much thought as hard worldbuilding – you just express that thought differently. Instead of explaining your world’s banking system, you might mention that your character’s sword was worth “three months of a dock worker’s wages.” Instead of detailing your magic system, you might show a character’s exhaustion after using magic, suggesting it has real costs without spelling them out.

The trick is choosing which ten percent to reveal. This isn’t random. You want to show the details that:

- Directly impact your plot

- Reveal character

- Create atmosphere

- Suggest the larger world without explaining it

Here’s my “Tuesday afternoon test” for soft worldbuilding. If someone from your world was having an ordinary Tuesday afternoon, what would they be doing? How would they think about their world? They wouldn’t be mentally reviewing the political structure or marveling at how magic works. They’d be worried about paying rent, wondering what to have for dinner, or dealing with interpersonal drama.

When you write from this perspective, worldbuilding details emerge naturally through character concerns rather than author exposition. Your protagonist doesn’t think “I activated my hereditary fire magic by channeling energy through my bloodline focus.” They think “I really hope this works” while trying not to burn down the building.

Pillar 2: Emotional Resonance Over Technical Accuracy

Soft worldbuilding prioritizes how things feel over how they work.

Your magic system doesn’t need to follow thermodynamics if it follows emotional logic. Your political system doesn’t need to mirror real-world governance if it creates the story tensions you need. Your geography can be impossible as long as it serves your themes.

This doesn’t mean anything goes. It means your internal consistency should serve emotional truth rather than technical accuracy.

Consider Hayao Miyazaki’s approach in films like “Spirited Away” or “Howl’s Moving Castle.” The magical elements don’t follow systematic rules. They follow emotional and thematic logic. The bathhouse spirits represent different aspects of Japanese culture and environmental concerns. Howl’s castle moves because the story needs nomadic freedom and magical whimsy, not because there’s a detailed mechanical explanation.

The key is using sensory details to create believability. Don’t tell me how your flying carpets work. Tell me how the wind feels different at altitude, how the carpet’s fibers are worn smooth where countless hands have gripped them, how your character’s ears pop during rapid descents.

Readers don’t need to understand the engineering. They need to feel the experience.

Pillar 3: Reader Collaboration

The most powerful aspect of soft worldbuilding is what happens in your reader’s imagination.

When you leave gaps, readers naturally fill them with details that make sense to them. This creates investment because they’re actively participating in creating the world. They become collaborators rather than passive recipients of information.

But this requires trust. You have to believe your readers are intelligent enough to make reasonable assumptions. You have to resist the urge to explain everything just because you know the explanation.

I learned this the hard way with a fantasy novel where I’d developed an intricate monetary system based on different metals having magical properties. I spent paragraphs explaining how “silver drakes” were worth more in some regions due to local magical traditions. My critique group glazed over.

The solution was simple. I cut the explanation and just had characters argue over payment, mention the exchange rate casually, and show frustration with currency conversion. Readers understood there was a complex system without needing the lecture. More importantly, they stayed engaged with the story.

The danger zone is leaving plot-critical information unexplained. If your climax depends on specific worldbuilding rules, you need to establish those rules clearly. But everything else? Trust your readers to figure it out.

Soft Worldbuilding Techniques That Actually Work

Let me give you some concrete tools for implementing soft worldbuilding effectively.

The Casual Mention Technique This is where you reference larger worldbuilding elements in passing, without stopping to explain them. A character might say “I haven’t seen weather like this since the Year of Storms,” suggesting historical events without detailing them. Or someone might wear “Northland wool,” implying trade relationships and different regions without drawing maps.

The key is making these mentions feel natural to the characters while being evocative to readers. Characters shouldn’t sound like they’re reciting from a travel brochure. They should reference their world the way you reference yours – with unconscious familiarity.

Character Perspective Filtering Your point-of-view character becomes your worldbuilding filter. They notice what matters to them and ignore what doesn’t. A soldier notices fortifications and weapon quality. A merchant notices trade goods and economic indicators. A child notices things adults take for granted.

This creates natural limitations on exposition while revealing character. When your street-smart thief doesn’t understand the political implications of a noble’s marriage alliance, that ignorance becomes characterization rather than a worldbuilding failure.

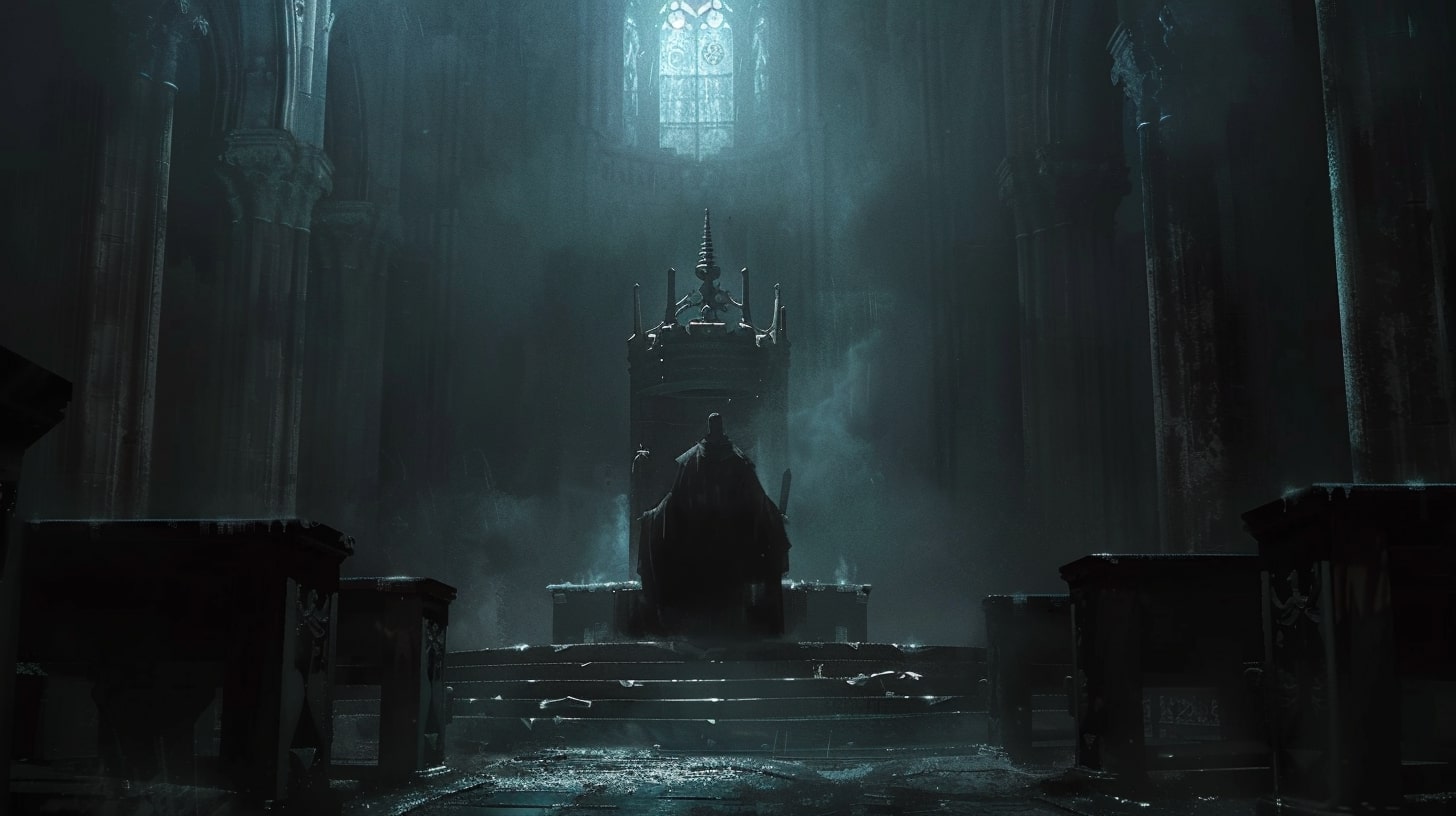

Environmental Storytelling Show your world’s history through physical details. Ancient scorch marks on stone walls suggest past conflicts. Worn grooves in stairs show centuries of use. Architectural styles reveal cultural values and available materials.

This technique lets you convey vast amounts of worldbuilding through observation rather than explanation. A city with narrow, twisted streets and buildings that lean inward suggests organic growth and defensive thinking. A city with wide boulevards and uniform architecture suggests central planning and administrative control.

Strategic Contradiction and Mystery Don’t explain everything consistently. Let some elements remain mysterious or contradictory. Maybe different characters have different explanations for the same phenomenon. Maybe some historical events have multiple conflicting accounts.

This mirrors how real people understand their world – incompletely, with gaps and uncertainties. It also gives you flexibility to develop details later without being locked into early explanations.

The Power of Implication Sometimes the best worldbuilding happens between the lines. If characters carry charms against “the night sickness,” you don’t need to detail the disease. The precaution implies its existence and danger. If someone refers to “the old laws” with distaste, you’ve suggested political history without exposition.

These implications let readers’ imaginations do the heavy lifting while you focus on story.

The Biggest Soft Worldbuilding Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

Even good writers screw up soft worldbuilding in predictable ways. Here are the major pitfalls and how to dodge them.

Mistake 1: Confusing Vague with Mysterious There’s a difference between intriguing ambiguity and lazy hand-waving. Mysterious elements should feel deliberately unexplained, with hints that suggest depth. Vague elements feel undefined because the author hasn’t thought them through.

The difference is specificity. Instead of saying magic is “ancient and powerful,” describe how using it leaves metallic taste in your mouth and makes your fingertips numb for hours. You’re not explaining the mechanism, but you’re giving concrete, specific details that make it feel real.

Mistake 2: Being Inconsistent vs. Being Selectively Detailed Soft worldbuilding doesn’t mean your details can contradict each other randomly. If you establish that magic users are rare, don’t suddenly populate your world with them without explanation. If you show technology at a certain level, don’t introduce anachronistic elements casually.

Consistency applies to the details you do reveal. Everything else can remain undefined until you need it.

Mistake 3: Leaving Plot-Critical Elements Unexplained The biggest soft worldbuilding failure is leaving readers confused about something essential to understanding your story. If your climax depends on specific magical rules, establish those rules earlier. If your character’s motivation requires understanding their cultural background, provide that context.

Soft worldbuilding works for flavor and atmosphere. It doesn’t work for plot mechanics.

Mistake 4: Assuming Soft Means Less Work Soft worldbuilding can actually require more skill than hard worldbuilding. You need to understand your world deeply enough to know which details to reveal and which to hide. You need to trust your instincts about reader psychology. You need to resist the urge to show off your creativity through exposition.

It’s like good acting. The best performances look effortless because the actor has done enormous preparation that doesn’t show on screen.

When Soft Worldbuilding Serves Your Story Best

Soft worldbuilding isn’t appropriate for every story, but it excels in specific situations.

Character-driven narratives benefit from soft worldbuilding because it keeps focus on internal journeys rather than external systems. If your story is about personal growth, relationship dynamics, or psychological exploration, elaborate worldbuilding can distract from emotional development.

Literary fantasy and magical realism often use soft worldbuilding to create dreamlike or metaphorical landscapes. The world serves symbolic rather than literal functions, so technical accuracy matters less than emotional or thematic resonance.

When your world is backdrop rather than focus, soft worldbuilding prevents scene-setting from overwhelming story-telling. The setting should support your narrative without competing for attention.

Cosmic or incomprehensible elements work better with soft worldbuilding because full explanation would diminish their mystery or exceed human understanding. Lovecraftian horror relies on the unknowable staying unknown.

First-person narratives with limited POV naturally suit soft worldbuilding because readers can only know what the narrator knows. If your protagonist doesn’t understand how their world works, neither do your readers – and that limitation can create suspense and identification.

Practical Implementation: Your Soft Worldbuilding Toolkit

Here are concrete techniques for implementing soft worldbuilding in your writing.

The Suggestion Journal Keep a separate document where you note worldbuilding details that exist but don’t appear in your story. This gives you a foundation for subtle references without cluttering your narrative. When characters mention “the eastern trade routes,” you know what they’re talking about even if readers don’t need the full explanation.

Creating Your Hidden Iceberg For every worldbuilding element that appears in your story, develop ten times more detail than you’ll use. This depth will show through consistent, casual references that suggest larger knowledge without requiring exposition.

Testing with Readers Beta readers are crucial for soft worldbuilding because you need to know when you’ve crossed the line from mysterious to confusing. If readers consistently misunderstand plot-relevant elements, you need more clarity. If they consistently ask for explanations of atmospheric details, you might be doing soft worldbuilding correctly.

Balancing Mystery with Clarity Create a hierarchy of information. Plot-essential elements need clarity. Character motivation requires enough context for understanding. Everything else can remain suggestive rather than explicit.

Resisting the Urge to Explain This is the hardest part. When you’ve created something clever, you want to show it off. When readers ask questions, you want to answer them. Sometimes the better choice is leaving things unexplained, trusting that the mystery serves your story better than the revelation.

Trusting the Process (and Your Readers)

Soft worldbuilding requires courage.

It’s scary to leave things unexplained when you know the explanation. It’s tempting to add “just one more detail” to make things clearer. It’s hard to trust that readers will fill gaps intelligently rather than getting confused or frustrated.

But here’s what I’ve learned after years of both over-explaining and under-explaining: readers are smarter than we give them credit for, and they prefer being trusted to figure things out over being lectured about details they didn’t ask for.

The best soft worldbuilding feels inevitable rather than arbitrary. It creates the sense of a larger world without the burden of understanding every piece of it. It lets readers focus on story and character while still feeling immersed in a believable reality.

Your world doesn’t need to be completely built. It needs to feel completely real. And sometimes, the things we don’t say carry more weight than the things we do.

Trust your readers. Trust your instincts. And remember that the most powerful worldbuilding often happens in the spaces between your words, where imagination meets suggestion and creates something larger than either could achieve alone.

The world you don’t show is just as important as the world you do. Make sure you’re leaving room for both.